The Tenement City’: The ‘Inconvenient' Urban Reality Facing Nairobi

Cross-posted from Living The City: Urban Informality

By Baraka Mwau, SDI

"When the modern city does not adapt to the people…The People will adapt to the city” (Urban Think Tank, Trailer-Torre David: the World’s Tallest Squat)

Living in the Tenements of Nairobi – Part One

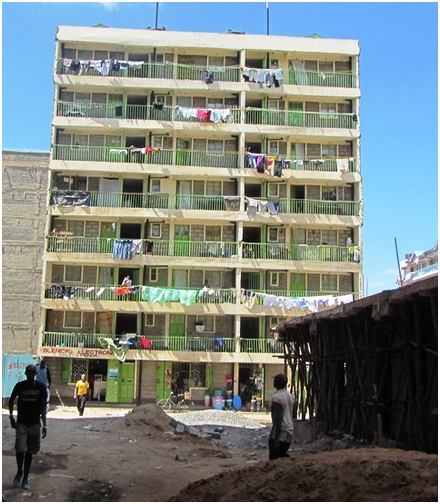

Tenements, or if used informally vertical semi-slums, are in their own version congested settlements which have been around since the industrial age and have been witnessed in all regions of the world, and especially in particular urban growth stages. These settlements, often strategically located near key urban services (mostly commercial areas) are a representation of the role of market forces in housing provision for a particular class of urban residents. These settlements maximize space use (mostly by exploiting ground coverage and plot ratio standards) and leverage huge capital investments with many housing units for which residents pay “affordable” rents. Like in many parts of the world, this phenomenon is rive in Nairobi, the capital city of Kenya and one of the fastest growing cities in Africa. In this article and its subsequent series, we will highlight various aspects of living in tenement buildings in Nairobi as told by individual dwellers.

It is 5 am on Saturday May 11 2013 in Pipeline Estate, Embakasi – Nairobi, one of the most notorious areas for unregularised tenements in the city. Milcah Kioko* (not her real name) has just woken up. No, it isn’t an early day because she has to report to “work”. Throughout her stay in the city, a day must start early, regardless of the fact that she is a housewife. Milka is however somewhat optimistic about landing a reliable job someday that will enable her to support her husband and combat the ruthless and indiscriminative escalating living cost in Nairobi. Having migrated from Eastern Kenya a few years ago to the city, she started urban life in a Nairobi slum, Mukuru kwa Njenga, where she was lucky to be sheltered by her elder married sister while looking for a job. Many slum residents can narrate how agonizing life can be for rural converts, making a fresh start in Nairobi slums. Without critical social networks, such as Milcah’s, the ‘arrival city’ (slums) can turn out to be one legendary, horror narrative to pass to your descendants. Even after being nested by her sister and tirelessly hunting for a reliable job for years, Milka has made very little progress. After the first few years, she had to leave the nest and continue with her job hunt from somewhere else, a move that opened a new chapter in her life. She got married and shifted focus to raising her young family. Life might have improved after her husband managed to move the family from Mukuru kwa Njenga slum to the adjacent ‘concrete jungle’, the high-rise tenements of Pipeline Estate, Embakasi.

Since her move, waking up early is Milka’s Saturday routine. The day normally begins by climbing down the sharply-inclined staircase from her unit on the sixth floor to the ground floor, where she joins the long queue at the water tap. Having migrated from the dry lands of Eastern Kenya, queuing for water is ‘normal’. She migrated from her rural home in the quest of living the ‘urban dream’ and creating a new ‘normal’ life. It’s almost a decade now, and the city still seems unforgiving to her.

Being a Saturday, her two young daughters are in slumberland until mid the morning. It’s not a school day and in any case, they have nowhere to play, except the dangerous and narrow balcony at their doorstep. This is highly unappealing for the kids. The numerous warnings they have received from their mother not to play near the balcony as well as the obvious physical danger has cultivated sufficient fear in them. They have also adapted to routine everyday re-organization of the house. The family lives in a single room, which similarly to a shack, is partitioned by a curtain and is accustomed to space-use transformation at different times of the day. After getting her water, Milcah is going to undertake a makeover of this temporal children bedroom to the living room and the kitchen.

The queue at the tap is long, taking several loops on the open-indoor space at the ground floor. You are never too early for it, unless you have a ‘good relationship’ with the building caretaker, who sends signals to his ‘friendly tenants’ when he is about to open the tap. That’s how powerful this position can be in these kinds of tenement buildings where communal facilities exist and infrastructure services are rationed. Often, the caretaker (mostly men) doesn’t send the signals for free; there are ‘payments’ involved. The ‘payments’ range from cash money to a beer in the bar at the ground floor and/or more ‘personalised’ forms from certain female tenants. This system is a clear illustration of how survival in tenements can be constructed through social networks. In these residences, the city council and utility companies are partially to blame for the inadequacy of services. The other half involves complex dealings with all sorts of actors, mainly including the landlord, property care taker, utility company workers, and service cartels.

Milcah has no choice but to join the queue and get her usual ration—4 jerricans (20 litres each). She is no party to the ‘exclusive club’ in the building, hence no favours from the care taker. As an offer of support, her husband will give her a hand in ferrying the water to their unit in the sixth floor, before he goes for work. Despite the building exceeding 4 floors (recommended threshold for a lift in Kenya), this particular building does not have a lift.

Her husband will also help to ferry the household solid waste (collected into a polythene bag) to dump it somewhere along the road side, on his way to work. Solid waste collection is yet another scarce service here. At least the City Council will pick up that garbage, when the ‘mountain’ gets visible enough.

The building used to have a booster pump which pumped water from the mains at the ground floor to the 7th floor. However, this pump worked only for a few months when the building was new. After its starting to malfunction, the landlord did not bother to repair or replace it. Surprisingly, Milcah is not even aware that there was such a pump in the building, even after living there for over a year. She is actually surprised that water indeed flowed in the taps and shared toilets/ bathrooms beyond the ground floor. It is not that she is ignorant, she just copes with the situation as is, and is motivated by the fact that her rent is just worth what she gets.

In most tenements, the utility bills (mainly water and electricity) are inclusive in the rent and only the landlord knows what goes to the service providers. In roomed tenements, sharing of toilets and bathrooms is the norm. The maintenance of these shared facilities is in most cases left to the tenants. Where there is no proper ‘maintenance plan’ formulated and followed by the tenants, the ‘tragedy of the commons’ triumphs. Should the later prevail, chances are that some tenement residents will find themselves grappling with the dilemma of ‘to have or to avoid guests’, just as it has been narrated by numerous shack residents. The dignified visitors could easily loathe the reception at the “small rooms”, especially those coming from upmarket areas. In most cases tenants develop a duty rooster for maintaining common spaces and facilities. Its not surprising to see tenants being actively engaged in managing the asset for the landlord, to whom they pay rent. For them, the free service they offer semi-consciously for the landlord is more to their benefit, and particularly in safe guarding their public health.

Similar to shack areas, infrastructure services in most tenements are constrained, either as a result of collapsed (or on the verge of collapse) building infrastructure, or inefficacies of the service provider. For electricity, the stories are agonizing as well and particularly in buildings where billing is on a shared meter. In these areas, meter reading is classified information that should only be known to three parties – the service provider, the care taker and the landlord. If not rationed by hours, the voltage limit will not permit tenants like Milcah to use certain appliances such as iron boxes, cookers, water heaters etc.

Milcah’s experience is just a tip of the iceberg. Life in Nairobi’s tenements is deeply dynamic and cannot be covered enough within the scope of this article. Mathare-Huruma, Pipeline, Zimmerman, Githurai, Roysambu and Kawangware neighbourhoods epitomize the tenement phenomenon in Nairobi. In these areas, buildings have plot coverage’s of 100% and plot ratios of upto 10 times the recommended standards. Yes, the buildings are built back-to-back, from beacon-to-beacon, go as high as 8floors, and use designs, shapes and space standards that can never be found anywhere else. The vertical densities in these neighbourhoods are extreme, filled with densely massed multi-storey buildings. The facades often decorated by hanging clothes or repugnant like windows that appear as engraved rather than fitted, and at times a view from the street will land on a solid wall.

In tenement areas, social life is influenced by the codes stipulated by landlords to tenants, and fully enforced by the tenants, such as locking the gate or the main entrance at certain times of the night.

The roads in these areas are rough and dusty. When it rains, they turn to muddy streets making walking and driving unbearable. Space convertibility is a key element in these areas, with streets converting into busy business areas in the mornings and evenings. During these times of day, the massive activities taking place on the main streets leading to public transport stops often mimic mass migration.

Subsequent series to this article will illustrate some of the urban qualities produced by tenements, the variety in housing they offer, their production and perhaps their implication to the urban future in Nairobi.