When more than half a city's people live in locations they have no rights to, without safe water or toilets, the solution cannot just be to have more projects—housing, water, or health. It must be about getting these residents involved in improving their neighbourhoods.

what we do

The issues

Slums occupy two per cent of Nairobi’s land, yet they are home to half the city’s population. In Kenya since the 1990s the city space occupied by the poorer half of its population has not increased. While informal settlements’ populations may have doubled in this time, the rate and scale of improvements have failed to match unrelenting densification and consolidation.

The slum is a part of the city and two sustain each other. In Kenya, informal settlements represent a tremendous resource, without which the city economy would grind to a halt. They are markets for industry, they provide low cost accommodation, schooling, health care, recreation for the mass of the city’s workers (and childcare, cooking, and cleaning for most middle and high income homes). They are a vital link between urban and rural economies and a city safety net.

Current mainstream thinking has lost this logic of inclusivity, instead reducing slum communities to beneficiaries of faulty visioning that obscuring the complexity of informal communities and offers to fix the problem with ‘decent housing’.

Our approach

Muungano calls for slum-friendly cities—we know that informality is not always a problem.

While the state has its project and procurement frameworks, Muungano draws its methodology from SDI, and particularly SDI’s Indian experiences.

Muungano’s upgrading experience shows that different slum situations will require different mixes of design variables – for instance, some projects will be in situ and some have to be done on green field locations. The only consistent variable, which is also the most significant difference between Muungano and state design, is the role of the community.

Muungano’s offering on community participation falls outside conventional project management frameworks and state-applied structures. It is an assurance that slum upgrading is possible, but only where communities themselves are at the centre of their development.

Where we work

The federation works at two levels: within slum communities, and at wider city and national scales.

Within slum communities

Muungano introduces and supports a way for the communities to organize themselves so that they can upgrade their settlements. Within each slum the federation brings together (mainly) women to form community savings groups. It then supports the savings group to catalyze broader community discussions and initiatives on improving the settlements. In order to do this, savings groups undertake household surveys, facilitate community planning forums, engage local authorities, and design ways for the community to pool together their resources to undertake projects.

City or national scale

The movement sustains pressure on cities to address the challenge of inadequate access to water, sanitation, drainage and other services, and the lack opportunities to improve the low cost housing stock which slums represent. In order to do this, the movement builds city slum profiles, federates slum saving group networks across cities and regions, and works with city authorities to design projects, undertake policy changes, and secure city funding.

How we work

In order to reach the large number of slum settlements across Kenya in an effective way, Muungano has systematized its methodology. The alliance seeks to build collective capacity in urban poor communities, using bottom-up tools such as community savings, development of resident associations, settlement- and city-wide data collection, peer exchanges and learning, community-led project design and implementation, and strategic partnerships with county and central government.

Nakuru West network savings group meeting. Photo: KYC TV

Community savings

By bringing together women in slum communities to save collectively and hold regular meetings, the movement can establish a community vehicle for development that is always present in the community, has a deep understanding of the community needs, and does not require external resources to sustain its efforts.

The basic unit of organization for Muungano is the community saving scheme. Muungano organizes along geographic incidence of informality—savings schemes draw their membership from the settlements or informal market where they are established. As a tool for mobilization, community savings change the basis of participation by creating space for women, tenants, youth, and other people who would ordinarily often be excluded.

Savings schemes will have varying membership—as small as 25 members, up to 1000 members, with an average of 40 members. Typically, the schemes are registered as self help groups. The principal goal of the saving scheme is to catalyze and provide agency to resident forums or platforms—similar to the resident associations (below)—which become the vehicles through which change is pursued and achieved.

Kisumu settlement meeting

Settlement residents’ associations

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution and legislation derived from the constitution set a high threshold for citizen participation in planning, budgeting, and other civic matters. In response, the Muungano Alliance has developed a social mobilization tool, to mobilize households in informal settings.

Our framework leverages on the recommended government public participation structure known as Nyumba Kumi ('ten households'), which aims to devolve community engagement to a basic unit of ten households. Muungano animates this model using a tool we have dubbed Tujuane Tujengane Mtaani ('let's know and build each other, in our own street').

The Tujuane Tujengane Mtaani tool:

Develop a standardized physical address system for the community—all structures in informal settlements are assigned a door number.

Mobilize every ten households to nominate two representatives. These representatives are responsible for collecting and passing on information, and for facilitating discussion on issues that may affect the residents they represent.

Form 'cluster forums', made up of ten of the ten-household units (10x10=100 households). Cluster forums consolidate views from these households through the ten-household representatives—and then in turn send representation to a settlement-level residents’ association.

Develop a digital platform for information sharing and discussion.

Learning from Indian slum dwellers' federation. Photo: Joseph Muturu

Exchange and learning

Horizontal learning exchanges—between one urban poor community and another—is the alliance's most important learning strategy.

Support for individual groups is structured around local, national, and international exchanges. Annually, the alliance will facilitate over 400 local, inter-city, and international peer-to-peer exchanges.

Communities which are engaged in development activity learn best from each other. When one savings group has initiated a successful income-generating project, re-planned a settlement, or built a toilet block, the alliance enables groups to come together and learn from intra-network achievements.

The community exchange process builds on the logic that ‘doing is knowing’, and helps to develop strategy, skills and attitudes.

Horizontal exchanges also create a platform for learning that builds alternative community-based politics and 'expertise'—challenging the notion that development solutions must come from professionals. In this way, communities begin to view themselves as holding the answers to their own problems, rather than looking externally for professional help. The pool of knowledge generated through exchange programs becomes a collective asset.

Community data collection, Mombasa. Photo: SDI Kenya

Community enumeration

Household surveys undertaken by the community that identify and records 100 percent of structures and their use within a settlement.

Enumeration aims to create a widely shared understanding of the settlement and the issues it faces. Enumeration therefore provides an alternative, to political or market forces, as the basis for the community plans and development.

Similarly the data produced also becomes the basis for discussion with local authorities.

Community from Thika planning their settlement at the University of Nairobi. Photo: SDI Kenya

Community planning

Muungano has adopted several ways for communities to work with planners, architects, engineers and other professionals to co-produce housing or service point typologies as well as street or settlement layouts.

Depending on the planned output, processes of community dreaming, house modelling or urban planning studios are undertaken.

Relationship between a census & informal settlement profiling

Settlement-wide and citywide data collection

Over the last 20 years, the Muungano Alliance has developed its methodology for acquiring accurate data about informality.

At the city and county levels, the alliance undertakes slum profiles that identify and map the boundaries of all incidences of informality. The profiles capture a social economic baseline (consisting of 50 variables) for each of the identified settlements. Citywide profiles have been undertaken in Nairobi, Kisumu, Nakuru, Machakos, Makueni and Mombasa. (See below for more on our profiling methodology).

Where settlements have significant opportunities for improvement—or threats to their continued existence—the alliance undertakes household surveys and mapping for 100 per cent of the settlement.

The data tools serve as a platform for engagement with governments and other stakeholders involved in planning and setting policy for development in urban centres.

The tools also create the space for communities to identify developmental priorities, organize leadership, expose and mediate grievances between segments of the community, and cohere around future planning.

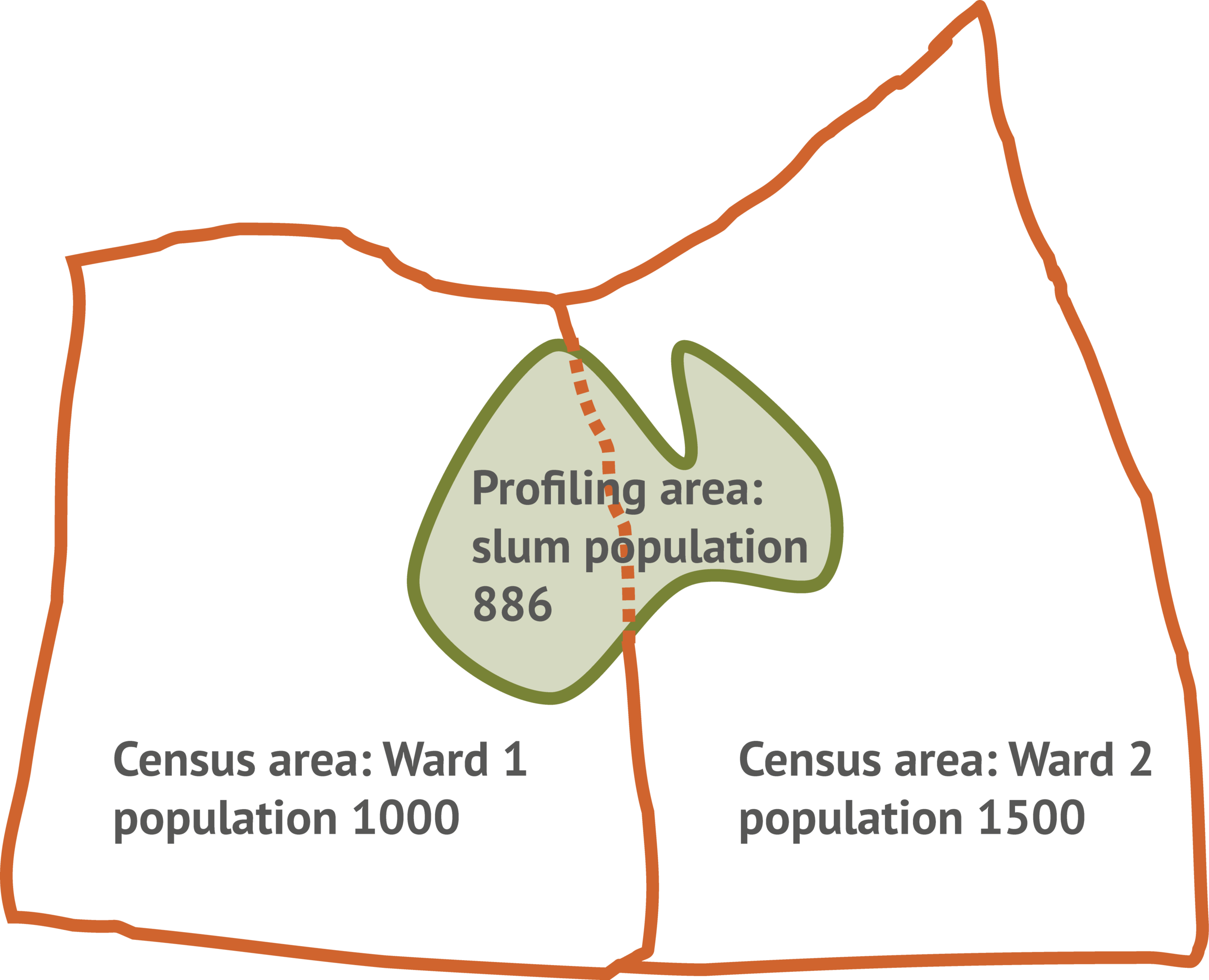

One of the main reasons the alliance has developed its data capability is that national and government censuses are unsuitable as a basis for addressing informality. Censuses are carried out in administrative units (locations, wards, sub- counties and so on). Informality does not align to such boundaries. Informal settlements often cut across administrative boundaries, or take up only parts of administrative units.

Almost invariably, national and county governments in Kenyan have no aggregated data on informality other than that which the Muungano alliance provides.

Looking out across part of Mathare valley. Photo: SDI Kenya

Citywide profiling of informal settlements

What is informal settlement profiling? Muungano’s citywide process for informal settlements profiling is similar to a government census. It focuses exclusively on informal settlements, but at a city scale. The aim of profiling is to build up a picture of poverty within the city where it takes place. Muungano's profiling produces data, maps, visuals, and statistical analysis about informality.

Typically, data on informality can't be derived from the national or city government census. These undertake counts based on administrative localities, and do not disaggregate formal and informal land use—especially where informality occurs on a section of an administrative unit, or cuts across administrative boundaries.

The data that Muungano's profiling makes available. Profiling targets every informal settlement in a city, producing a complete list of slums and informal open markets. A street map is generated for each settlement on the list, showing boundaries alongside adjacent roads or landmarks.